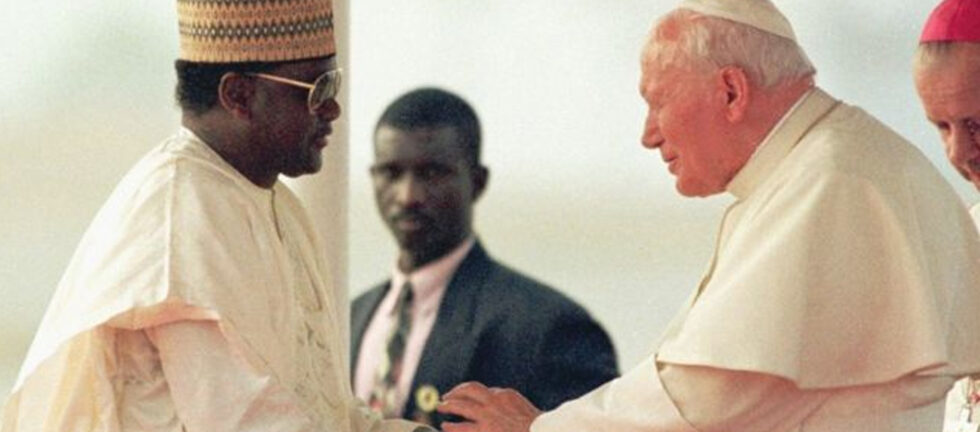

The Pope never bargained for such. It was purely a pastoral visit to Catholic Church in Nigeria. But the old man was to discover, to his chagrin, that Nigerians from all faiths and denominations, choking under the draconian rule of General Sani Abacha, were pinning their hopes on him to persuade the iron-fisted ruler, to let go the jugular of the nation.

As Pope John Paul II drove through the streets of Abuja, Nigeria’s new, shining capital city, enthusiastic spectators held up copies of the newspapers for him to see. POPE OUR LAST HOPE was the screaming banner headline of The Vanguard. Virtually all the newspapers cast SOS headlines and wrote passionate editorials and feature appealing to the Pontiff to persuade the head of state, General Sani Abacha to do the right thing: hand over power, not to himself, but to a democratically elected government; to release all politicians and journalists and respect human rights and human lives.

“Bail us out, Holy Father! Bail us out!” a group of youths cried out as the “Pope Mobile,” his transparent, custom-made SUV approached the city center. Simultaneously, welcome billboards, banners, and posters placed by the government along the expected routes of the Pope gave a different impression of a country practically under siege. Both the government and its critics were eager to gain the Pope’s ear and plead the merits of their case.

The first group was the association of Roman Catholic bishops and archbishops called the Catholics Bishops Conference of Nigeria who had already, on the eve of the pontiff’s visit, urged Gen. Abacha to free political prisoners and make amends with opposition groups. They told the Pope that they were not comfortable with the situation on the ground as the “Nigerian nation is critically ill” and suggested that in his meeting with Abacha he should stress the importance of dialogue and reconciliation. They also requested him to entreat the government to “release all political detainees and prisoners and allow them to participate fully in the transition process.” The Conference submitted to the Pope a list of 150 detained and imprisoned politicians, unionists, activists, and journalists for onward delivery to Abacha, with a request for him to release them.

The Pope also received a long memo from a group in the US known as the Nigerian Pro-Democracy Network, NPN, a coalition of pro-democracy organizations in various parts of the US. It told the Pope that, since Abacha came to power in November 1993, the entire country has been held hostage by a “systematic silencing of every dissenting voice,” including that of MKO Abiola, the winner of the 1993 Presidential elections. “Beginning with the political class, the regime has targeted labour leaders, intellectuals, journalists, students, human rights activists, and environmentalists,” the memo said. It cast doubts on the genuineness of Abacha’s transition to the civil rule program. The Pope would be doing the will of God to intervene, the NPN said.

An international group of journalists, Reporters Sans Frontiers told the Pope Nigeria was “one of the most repressive African countries with regard to freedom of the press”; that more than 90 journalists had suffered repression last year and “at present, six additional journalists are being detained without an official reason. Some of them are waiting to be tried and their health is said to be poor.” The group asked the Pope to intercede on the journalists’ behalf.

The Nigeria Civil Liberty Organization, leaders of Protestant churches, and families of detained activists, also placed their hopes in the Pope for a solution to Nigeria’s problems. And a group of women pleaded in their letter: “The rest of the world seems to have abandoned us in the hands of merciless soldiers. We have exhausted every means of securing the freedom of our husbands. Don’t go home, please, Your Holiness, without securing the release of our husbands.”

The government, however, also had every intention of taking the utmost propaganda advantage of the Pontiff’s visit, even naming two streets as Pope John Paul II Street and pope John Paul II Crescent. Loquacious Foreign Affairs Minister Tom Ikimi ensured that the Vatican envoy in Nigeria gave the Pope its side of the story. He was told of the “peace and stability” that the Abacha administration has secured for Nigeria since taking power.

Pope Pius II lived up to expectations. With no direct reference to the regime, the implications of his homilies were transparent. He repeated the same message publicly on two separate occasions, in Onitsha and Abuja, before a combined audience of more than five million.

At his reception ceremony and at the two outdoor Masses he spoke against injustice, dictatorship, military rule, and abuse of human rights. With reference to the official motives of the visit, the beatification of Father Cyprian Michael Tansi, the Pope declared: “The testimony borne by Father Tansi is important at this moment in Nigeria’s history, a moment that requires concerted and honest effort to foster harmony and national unity, to guarantee respect for human life and human rights.”

He recommended an “attitude of reconciliation” on the part of the government and the people as well as a “return to constitutional order and democratic freedom.”And in what was perhaps his closest sailing to the wind, he declared there could be no place “for intimidation and domination of the poor and the weak, arbitrary exclusion of individuals and groups from political life, misuse of authority or the abuse of power. Justice is not complete without an attitude of humble, generous service.”

In anticipation, the answers had no doubt been well-rehearsed. To the Pope’s call for “honest efforts to foster harmony, national unity and guarantee respect for human life and human rights,” General Abacha said his government needed “prayers to persevere in our task without discouragement.” To the call by the Pope for an “attitude of reconciliation” and “restoration of constitutional order and democratic freedom,” the dreaded General said his administration abhorred dictatorship; and the transition program which was being midwived by him would give birth to “a new era of stability.”

Behind closed doors at Aso Rock, the head of state’s official residence in Abuja, the Pope followed up with a list of 60 names of people who should be given freedom, perhaps the same names that had been given him by the archbishops and bishops. The list includes Chief Abiola; General Olusegun Obasanjo, former head of state; Frank Kokori, president of the oil workers’ union; Olu Falae, former Secretary to the Federal Government, and dozens of other politicians and journalists. Joachin Nevalro-Vaal, the Vatican spokesman, said the 60 names were “compiled by the Holy See” based on information from international organizations, detainees’ families, journalists, and the government. In Pope John Paul’s 82 missionary journeys outside Italy, this was only the second occasion on which he had presented such a list. The first time was to President Fidel Castro of Cuba who had acted upon it immediately.

That the Pope would succeed in Nigeria where other world leaders had failed remained no more than a hope. Pleas in the past for the release of political prisoners by Commonwealth Heads of State and others have been received with indifference. Abacha’s announcement last October during Nigeria’s Independence Anniversary that he was releasing political prisoners turned out to be a non-starter; not one political prisoner was released except General Shehu Yar’Adua, former deputy head of state, whose body was “released” for burial after he died in prison in suspicious circumstances last November.

Abacha-watchers and political observers believe the General may not listen to the papal supplications, except possibly on the issue of self-succession. But Catholic leaders in Nigeria were optimistic that the Papal pleas would not go unheeded. “His requests have never been rejected by any world leader nor by any faction or rebel leader. Nobody is known to have turned down the Pope,” is the sanguine reminder of Father Matthew Kukah, Secretary-General of the Catholic Secretariat in Nigeria.

But there was no immediate flinging open of the prison gates either during or in the immediate wake of the Pope’s departure.